CHAPTER 1 What Is Software Engineering?

第一章 软件工程是什么?

Written by Titus Winters

Edited by Tom Manshreck

Nothing is built on stone; all is built on sand, but we must build as if the sand were stone. --Jorge Luis Borges

We see three critical differences between programming and software engineering: time, scale, and the trade-offs at play. On a software engineering project, engineers need to be more concerned with the passage of time and the eventual need for change. In a software engineering organization, we need to be more concerned about scale and efficiency, both for the software we produce as well as for the organization that is producing it. Finally, as software engineers, we are asked to make more complex decisions with higher-stakes outcomes, often based on imprecise estimates of time and growth.

我们看到,编程和软件工程之间有三个关键的区别:时间、规模和权衡取舍。在一个软件工程项目中,工程师需要更多关注时间成本和需求变更。在软件工程中,我们需要更加关注规模和效率,无论是对我们生产的软件,还是对生产软件的组织。最后,作为软件工程师,我们被要求做出更复杂的决策,其结果风险更大,而且往往是基于对时间和规模增长的不确定性的预估。

Within Google, we sometimes say, “Software engineering is programming integrated over time.” Programming is certainly a significant part of software engineering: after all, programming is how you generate new software in the first place. If you accept this distinction, it also becomes clear that we might need to delineate between programming tasks (development) and software engineering tasks (development, modification, maintenance). The addition of time adds an important new dimension to programming. Cubes aren’t squares, distance isn’t velocity. Software engineering isn’t programming.

在谷歌内部,我们有时会说,"软件工程是随着时间推移的编程。"编程当然是软件工程的一个重要部分:毕竟,编程首先是生成新软件的方式。如果你接受这一区别,那么很明显,我们可能需要在编程任务(开发)和软件工程任务(开发、修改、维护)之间进行划分。时间的增加为编程增加了一个重要的新维度。这是一个立方体三维模型不是正方形的二维模型,距离不是速度。软件工程不是编程。

One way to see the impact of time on a program is to think about the question, “What is the expected life span1 of your code?” Reasonable answers to this question vary by roughly a factor of 100,000. It is just as reasonable to think of code that needs to last for a few minutes as it is to imagine code that will live for decades. Generally, code on the short end of that spectrum is unaffected by time. It is unlikely that you need to adapt to a new version of your underlying libraries, operating system (OS), hardware, or language version for a program whose utility spans only an hour. These short-lived systems are effectively “just” a programming problem, in the same way that a cube compressed far enough in one dimension is a square. As we expand that time to allow for longer life spans, change becomes more important. Over a span of a decade or more, most program dependencies, whether implicit or explicit, will likely change. This recognition is at the root of our distinction between software engineering and programming.

了解时间对程序的影响的一种方法是思考“代码的预期生命周期是多少?”这个问题的合理答案大约相差100,000倍。想到生命周期几分钟的代码和想象将持续执行几十年的代码是一样合理。通常,周期短的代码不受时间的影响。对于一个只需要存活一个小时的程序,你不太可能考虑其底层库、操作系统(OS)、硬件或语言版本的新版本。这些短期系统实际上“只是”一个编程问题,就像在一个维度中压缩得足够扁的立方体是正方形一样。随着我们扩大时间维度,允许更长的生命周期,改变显得更加重要。在十年或更长的时间里,大多数程序依赖关系,无论是隐式的还是显式的,都可能发生变化。这一认识是我们区分软件工程和编程的根本原因。

1We don’t mean “execution lifetime,” we mean “maintenance lifetime”—how long will the code continue to be built, executed, and maintained? How long will this software provide value?

[1] 我们不是指“开发生命周期”,而是指“维护生命周期”——代码将持续构建、执行和维护多长时间?这个软件能提供多长时间的价值?

This distinction is at the core of what we call sustainability for software. Your project is sustainable if, for the expected life span of your software, you are capable of reacting to whatever valuable change comes along, for either technical or business reasons. Importantly, we are looking only for capability—you might choose not to perform a given upgrade, either for lack of value or other priorities.2 When you are fundamentally incapable of reacting to a change in underlying technology or product direction, you’re placing a high-risk bet on the hope that such a change never becomes critical. For short-term projects, that might be a safe bet. Over multiple decades, it probably isn’t.3

这种区别是我们所说的软件可持续性的核心。如果在软件的预期生命周期内,你能够对任何有价值的变化做出反应,无论是技术还是商业原因,那么你的项目是可持续的。重要的是,我们只关注能力——你可能因为缺乏价值或其他优先事项而选择不进行特定的升级。当你基本上无法对基础技术或产品方向的变化做出反应时,你就把高风险赌注押在希望这种变化永远不会变得至关重要。对于短期项目,这可能是一个安全的赌注。几十年后,情况可能并非如此。

Another way to look at software engineering is to consider scale. How many people are involved? What part do they play in the development and maintenance over time? A programming task is often an act of individual creation, but a software engineering task is a team effort. An early attempt to define software engineering produced a good definition for this viewpoint: “The multiperson development of multiversion programs.”4 This suggests the difference between software engineering and programming is one of both time and people. Team collaboration presents new problems, but also provides more potential to produce valuable systems than any single programmer could.

另一种看待软件工程的方法是考虑规模。有多少人参与?随着时间的推移,他们在开发和维护中扮演什么角色?编程任务通常是个人的创造行为,但软件工程任务是团队的工作。早期定义软件工程的尝试为这一观点提供了一个很好的定义:“多人开发的多版本程序”。这表明软件工程和程序设计之间的区别是时间和人的区别。团队协作带来了新的问题,但也提供了比任何单个程序员更多的潜力来产生有价值的系统。

2This is perhaps a reasonable hand-wavy definition of technical debt: things that “should” be done, but aren’t yet—the delta between our code and what we wish it was.

2 这也许是一个合理且简单的技术债务定义:那些“应该”做却还未完成的事————我们代码的现状和理想代码之间的差距。

3Also consider the issue of whether we know ahead of time that a project is going to be long lived.

3 也要考虑我们是否提前知道项目将长期存在的问题。

4There is some question as to the original attribution of this quote; consensus seems to be that it was originally phrased by Brian Randell or Margaret Hamilton, but it might have been wholly made up by Dave Parnas. The common citation for it is “Software Engineering Techniques: Report of a conference sponsored by the NATO Science Committee,” Rome, Italy, 27–31 Oct. 1969, Brussels, Scientific Affairs Division, NATO.

4 关于这句话的原始出处有一些疑问;人们似乎一致认为它最初是由Brian Randell或Margaret Hamilton提出的,但它可能完全是由Dave Parnas编造的。这句话的常见引文是 "软件工程技术。由北约科学委员会主办的会议报告1969年10月27日至31日,意大利罗马,布鲁塞尔,北约科学事务司。

Team organization, project composition, and the policies and practices of a software project all dominate this aspect of software engineering complexity. These problems are inherent to scale: as the organization grows and its projects expand, does it become more efficient at producing software? Does our development workflow become more efficient as we grow, or do our version control policies and testing strategies cost us proportionally more? Scale issues around communication and human scaling have been discussed since the early days of software engineering, going all the way back to the Mythical Man Month. 5 Such scale issues are often matters of policy and are fundamental to the question of software sustainability: how much will it cost to do the things that we need to do repeatedly?

团队组织、项目组成以及软件项目的策略和实践都支配着软件工程复杂性。这些问题是规模所固有的:随着组织的增长和项目的扩展,它在生产软件方面是否变得更加高效?我们的开发工作流程随着我们的发展,效率会提高,还是版本控制策略和测试策略的成本会相应增加?从软件工程的早期开始,人们就一直在讨论沟通和人员的规模问题,一直追溯到《人月神话》。这种规模问题通常是策略的问题,也是软件可持续性问题的基础:重复做我们需要做的事情要花多少钱?

We can also say that software engineering is different from programming in terms of the complexity of decisions that need to be made and their stakes. In software engineering, we are regularly forced to evaluate the trade-offs between several paths forward, sometimes with high stakes and often with imperfect value metrics. The job of a software engineer, or a software engineering leader, is to aim for sustainability and management of the scaling costs for the organization, the product, and the development workflow . With those inputs in mind, evaluate your trade-offs and make rational decisions. We might sometimes defer maintenance changes, or even embrace policies that don’t scale well, with the knowledge that we’ll need to revisit those decisions. Those choices should be explicit and clear about the deferred costs.

我们还可以说,软件工程与编程的不同之处在于需要做出的决策的复杂性及其风险。在软件工程中,我们经常被迫在几个路径之间做评估和权衡,有时风险很高,而且价值指标不完善。软件工程师或软件工程负责人的工作目标是实现组织、产品和开发工作流程的可持续性和管理扩展成本为目标。考虑到这些投入,评估你的权衡并做出理性的决定。有时,我们可能会推迟维护更改,甚至接受扩展性不好的策略,因为我们知道需要重新审视这些决策。这些决策应该是明确的和清晰的递延成本。

Rarely is there a one-size-fits-all solution in software engineering, and the same applies to this book. Given a factor of 100,000 for reasonable answers on “How long will this software live,” a range of perhaps a factor of 10,000 for “How many engineers are in your organization,” and who-knows-how-much for “How many compute resources are available for your project,” Google’s experience will probably not match yours. In this book, we aim to present what we’ve found that works for us in the construction and maintenance of software that we expect to last for decades, with tens of thousands of engineers, and world-spanning compute resources. Most of the practices that we find are necessary at that scale will also work well for smaller endeavors: consider this a report on one engineering ecosystem that we think could be good as you scale up. In a few places, super-large scale comes with its own costs, and we’d be happier to not be paying extra overhead. We call those out as a warning. Hopefully if your organization grows large enough to be worried about those costs, you can find a better answer.

在软件工程中很少有一刀切的解决方案,这本书也是如此。考虑到“这个软件能使用多久”的合理答案是100,000倍,而“你的组织中有多少工程师”的范围可能是10,000,谁知道“你的项目有多少计算资源可用”的范围是多少,谷歌的经验可能与你的经验不一致。在本书中,我们的目标是介绍我们在构建和维护软件方面的发现,这些软件预计将持续数十年,拥有数万计的工程师和遍布世界的计算资源。我们发现在这种规模下所需要的大多数做法也能很好地适用于复杂度较小的系统:考虑一下这是一个我们认为在你们扩大的时候可以做的很好的工程生态系统的报告。在一些地方,超大规模有其自身的成本,我们更倾向于不付出额外的管理成本。我们发出警告。希望如果你的组织发展到足以担心这些成本,你可以找到更好的答案。

Before we get to specifics about teamwork, culture, policies, and tools, let’s first elaborate on these primary themes of time, scale, and trade-offs.

在我们讨论团队合作、文化、策略和工具的细节之前,让我们首先阐述一下时间、规模和权衡这些主要主题。

5Frederick P. Brooks Jr. The Mythical Man-Month: Essays on Software Engineering (Boston: Addison-Wesley, 1995)

Frederick P. Brooks Jr. The Mythical Man-Month: 关于软件工程的论文(波士顿:Addison-Wesley,1995)。

Time and Change 时间与变化

When a novice is learning to program, the life span of the resulting code is usually measured in hours or days. Programming assignments and exercises tend to be write- once, with little to no refactoring and certainly no long-term maintenance. These programs are often not rebuilt or executed ever again after their initial production. This isn’t surprising in a pedagogical setting. Perhaps in secondary or post-secondary education, we may find a team project course or hands-on thesis. If so, such projects are likely the only time student code will live longer than a month or so. Those developers might need to refactor some code, perhaps as a response to changing requirements, but it is unlikely they are being asked to deal with broader changes to their environment.

当新手学习编程时,编码的生命周期通常以小时或天为单位。编程作业和练习往往是一次编写的,几乎没有重构,当然也没有长期维护。这些程序通常在初始生产后不再重建或再次执行。这在教学环境中并不奇怪。也许在中学或中学后教育,我们可以找到团队项目课程或实践论文。如果是这样的,项目很可能是学生们的代码生命周期超过一个月左右的时间。这些开发人员可能需要重构一些代码,也许是为了应对不断变化的需求,但他们不太可能被要求处理环境的更大变化。

We also find developers of short-lived code in common industry settings. Mobile apps often have a fairly short life span,6 and for better or worse, full rewrites are relatively common. Engineers at an early-stage startup might rightly choose to focus on immediate goals over long-term investments: the company might not live long enough to reap the benefits of an infrastructure investment that pays off slowly. A serial startup developer could very reasonably have 10 years of development experience and little or no experience maintaining any piece of software expected to exist for longer than a year or two.

我们还在常见的行业环境中找到短期代码的开发人员。移动应用程序的生命周期通常很短,而且无论好坏,完全重写都是相对常见的。初创初期的工程师可能会正确地选择关注眼前目标而不是长期投资:公司可能活得不够长,无法从回报缓慢的基础设施投资中获益。一个连续工作多年的开发人员可能有10年的开发经验,并且鲜少或根本没有维护任何预期存在超过一年或两年的软件的经验。

On the other end of the spectrum, some successful projects have an effectively unbounded life span: we can’t reasonably predict an endpoint for Google Search, the Linux kernel, or the Apache HTTP Server project. For most Google projects, we must assume that they will live indefinitely—we cannot predict when we won’t need to upgrade our dependencies, language versions, and so on. As their lifetimes grow, these long-lived projects eventually have a different feel to them than programming assignments or startup development.

另一方面,一些成功的项目实际上有无限的生命周期:我们无法准确地预测Google搜索、Linux内核或Apache HTTP服务器项目的终点。对于大多数谷歌项目,我们必须假设它们将无限期地存在,我们无法预测何时不需要升级依赖项、语言版本等。随着他们生命周期的延长,这些长期项目最终会有一种不同于编程任务或初创企业发展不同的感受。

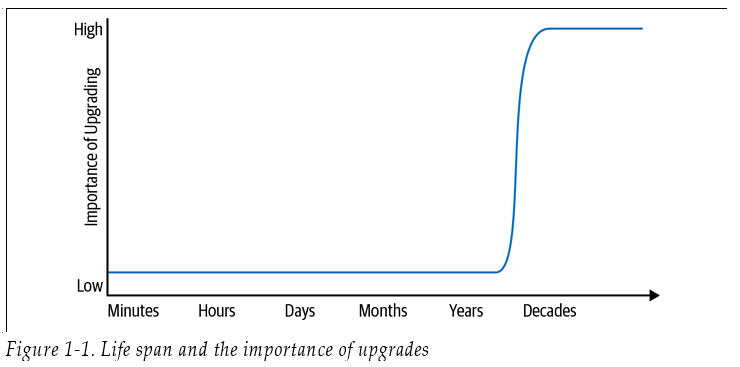

Consider Figure 1-1, which demonstrates two software projects on opposite ends of this “expected life span” spectrum. For a programmer working on a task with an expected life span of hours, what types of maintenance are reasonable to expect? That is, if a new version of your OS comes out while you’re working on a Python script that will be executed one time, should you drop what you’re doing and upgrade? Of course not: the upgrade is not critical. But on the opposite end of the spectrum, Google Search being stuck on a version of our OS from the 1990s would be a clear problem.

考虑图1-1,它演示了两个软件项目的“预期生命周期”的范围。对于从事预期生命周期为小时的任务的程序来说,什么类型的维护是合理的?也就是说,如果你正在编写一个只需执行一次的 Python 脚本,这时操作系统推出了新版本,你应该放下手头的工作去升级系统吗?当然不是:升级并不重要。但与之相反,如果谷歌搜索停留在20世纪90年代的操作系统版本上显然是一个问题。

6Appcelerator, “Nothing is Certain Except Death, Taxes and a Short Mobile App Lifespan,” Axway Developer blog, December 6, 2012.

除了死亡、税收和短暂的移动应用生命,没有什么是确定的

The low and high points on the expected life span spectrum suggest that there’s a transition somewhere. Somewhere along the line between a one-off program and a project that lasts for decades, a transition happens: a project must begin to react to changing externalities.7 For any project that didn’t plan for upgrades from the start, that transition is likely very painful for three reasons, each of which compounds the others:

- You’re performing a task that hasn’t yet been done for this project; more hidden assumptions have been baked-in.

- The engineers trying to do the upgrade are less likely to have experience in this sort of task.

- The size of the upgrade is often larger than usual, doing several years’ worth of upgrades at once instead of a more incremental upgrade.

预期生命周期范围的低点和高点表明某处有一个过渡。介于一次性计划和持续十年的项目,发生了转变:一个项目必须开始对不断变化的外部因素做出反应。对于任何一个从一开始就没有升级计划的项目,这种转变可能会非常痛苦,原因有三个,每一个都会使其他原因变得复杂:

- 你正在执行本项目尚未完成的任务;更多隐藏的假设已经成立。

- 尝试进行升级的工程师不太可能具有此类任务的经验。

- 升级的规模通常比平时大,一次完成几年的升级,而不是增量升级。

And thus, after actually going through such an upgrade once (or giving up part way through), it’s pretty reasonable to overestimate the cost of doing a subsequent upgrade and decide “Never again.” Companies that come to this conclusion end up committing to just throwing things out and rewriting their code, or deciding to never upgrade again. Rather than take the natural approach by avoiding a painful task, sometimes the more responsible answer is to invest in making it less painful. It all depends on the cost of your upgrade, the value it provides, and the expected life span of the project in question.

因此,在经历过一次升级(或中途放弃)之后,高估后续升级的成本并决定“永不再升级”是非常合理的。得出这个结论的公司最终承诺放弃并重写代码,或决定不再升级。有时,更负责任的答案不是采取常规的方法避免痛苦的任务,而是投入资源用于减轻痛苦。这一切都取决于升级的成本、提供的价值以及相关项目的预期生命周期。

7Your own priorities and tastes will inform where exactly that transition happens. We’ve found that most projects seem to be willing to upgrade within five years. Somewhere between 5 and 10 years seems like a conservative estimate for this transition in general.

7 你自己的优先次序和品味会告诉你这种转变到底发生在哪里。我们发现,大多数项目似乎愿意在五年内升级。一般来说,5到10年似乎是这一转变的保守估计。

Getting through not only that first big upgrade, but getting to the point at which you can reliably stay current going forward, is the essence of long-term sustainability for your project. Sustainability requires planning and managing the impact of required change. For many projects at Google, we believe we have achieved this sort of sustainability, largely through trial and error.

不仅完成了第一次大升级,而且达到可靠地保持当前状态的程度,这是项目长期可持续性的本质。可持续性要求规划和管理所需变化的影响。对于谷歌的许多项目,我们相信我们已经实现了这种持续能力,主要是通过试验和错误。

So, concretely, how does short-term programming differ from producing code with a much longer expected life span? Over time, we need to be much more aware of the difference between “happens to work” and “is maintainable.” There is no perfect solution for identifying these issues. That is unfortunate, because keeping software maintainable for the long-term is a constant battle.

那么,具体来说,短期编程与生成预期生命周期更长的代码有何不同?随着时间的推移,我们需要更多地意识到“正常工作”和“可维护”之间的区别。识别这些问题没有完美的解决方案。这是不幸的,因为保持软件的长期可维护性是一场持久战。

Hyrum’s Law 海勒姆定律

If you are maintaining a project that is used by other engineers, the most important lesson about “it works” versus “it is maintainable” is what we’ve come to call Hyrum’s Law:

*With a sufficient number of users of an API, it does not matter what you promise in the contract: all observable behaviors of your system will be depended on by somebody.*

如果你正在维护一个由其他工程师使用的项目,那么关于“有效”与“可维护”最重要的一课就是我们所说的海勒姆定律:

*当一个 API 有足够多的用户的时候,在约定中你承诺的什么都无所谓,所有在你系统里面被观察到的行为都会被一些用户直接依赖。*

In our experience, this axiom is a dominant factor in any discussion of changing software over time. It is conceptually akin to entropy: discussions of change and maintenance over time must be aware of Hyrum’s Law8 just as discussions of efficiency or thermodynamics must be mindful of entropy. Just because entropy never decreases doesn’t mean we shouldn’t try to be efficient. Just because Hyrum’s Law will apply when maintaining software doesn’t mean we can’t plan for it or try to better understand it. We can mitigate it, but we know that it can never be eradicated.

根据我们的经验,这个定律在任何关于软件随时间变化的讨论中都是一个主导因素。它在概念上类似于熵:对随时间变化和维护的讨论必须了解海勒姆定律,正如对效率或热力学的讨论必须注意熵一样。仅仅因为熵从不减少并不意味着我们不应该努力提高效率。在维护软件时,"海勒姆定律 "会适用,但这并不意味着我们不能对它进行规划或试图更好地了解它。我们可以减轻它,但我们知道,它永远不可能被根除。

Hyrum’s Law represents the practical knowledge that—even with the best of intentions, the best engineers, and solid practices for code review—. As an API owner, you will gain some flexibility and freedom by being clear about interface promises, but in practice, the complexity and difficulty of a given change also depends on how useful a user finds some observable behavior of your API. If users cannot depend on such things, your API will be easy to change. Given enough time and enough users, even the most innocuous change will break something;9 your analysis of the value of that change must incorporate the difficulty in investigating, identifying, and resolving those breakages.

海勒姆定律体现了实际知识,即便有良好的意图、顶尖的工程师和扎实的代码审查流程,也不能保证完全遵守契约或最佳实践。作为API所有者,通过明确地接口约定,你将获得一定的灵活性和自由度,但在实践中,给定更改的复杂性和难度还取决于用户对你的API的一些可观察行为的有用程度。如果用户不能依赖这些东西,那么你的API将很容易更改。如果有足够的时间和足够的用户,即使是最无害的变更也会破坏某些东西;你对变更价值的分析必须包含调查、识别和解决这些缺陷的难度。

8To his credit, Hyrum tried really hard to humbly call this “The Law of Implicit Dependencies,” but “Hyrum’s Law” is the shorthand that most people at Google have settled on.

值得称道的是,海勒姆非常努力地将其称为 "隐性依赖定律",但 "海勒姆定律 "是谷歌公司大多数人都认可的简称。

9See “Workflow,” an xkcd comic.

见 "工作流程",一幅xkcd漫画。

Example: Hash Ordering 哈希排序

Consider the example of hash iteration ordering. If we insert five elements into a hash-based set, in what order do we get them out?

考虑哈希迭代排序的例子。如果我们在一个基于散列的集合中插入五个元素,我们将以什么顺序将它们取出?

>>> for i in {"apple", "banana", "carrot", "durian", "eggplant"}: print(i)

...

durian

carrot

apple

eggplant

banana

Most programmers know that hash tables are non-obviously ordered. Few know the specifics of whether the particular hash table they are using is intending to provide that particular ordering forever. This might seem unremarkable, but over the past decade or two, the computing industry’s experience using such types has evolved:

- Hash flooding10 attacks provide an increased incentive for nondeterministic hash iteration.

- Potential efficiency gains from research into improved hash algorithms or hash containers require changes to hash iteration order.

- Per Hyrum’s Law, programmers will write programs that depend on the order in which a hash table is traversed, if they have the ability to do so.

大多数程序员都知道哈希表是无序的。很少有人知道他们使用的特定哈希表是否打算永远提供特定的排序。这似乎不起眼,但在过去的一二十年中,计算行业使用这类类型的经验不断发展:

- 哈希洪水攻击增加了非确定性哈希迭代的动力。

- 研究改进的散列算法或散列容器的潜在效率收益需要更改散列迭代顺序。

- 根据海勒姆定律,如有能力程序员可根据哈希表的遍历顺序编写程序。

As a result, if you ask any expert “Can I assume a particular output sequence for my hash container?” that expert will presumably say “No.” By and large that is correct, but perhaps simplistic. A more nuanced answer is, “If your code is short-lived, with no changes to your hardware, language runtime, or choice of data structure, such an assumption is fine. If you don’t know how long your code will live, or you cannot promise that nothing you depend upon will ever change, such an assumption is incorrect.” Moreover, even if your own implementation does not depend on hash container order, it might be used by other code that implicitly creates such a dependency. For example, if your library serializes values into a Remote Procedure Call (RPC) response, the RPC caller might wind up depending on the order of those values.

因此,如果你问任何一位专家“我能为我的散列容器有特定的输出序列吗?”这位专家大概会说“不”。总的来说,这是正确的,但过于简单。一个更微妙的回答是,“如果你的代码是短期的,没有对硬件、语言运行时或数据结构的选择进行任何更改,那么这样的假设是正确的。如果你不知道代码的生命周期,或者你不能保证你所依赖的任何东西都不会改变,那么这样的假设是不正确的。”,即使你自己的实现不依赖于散列容器顺序,也可能被隐式创建这种依赖关系的其他代码使用。例如,如果库将值序列化为远程过程调用(RPC)响应,则RPC调用程序可能会根据这些值的顺序结束。

This is a very basic example of the difference between “it works” and “it is correct.” For a short-lived program, depending on the iteration order of your containers will not cause any technical problems. For a software engineering project, on the other hand, such reliance on a defined order is a risk—given enough time, something will make it valuable to change that iteration order. That value can manifest in a number of ways, be it efficiency, security, or merely future-proofing the data structure to allow for future changes. When that value becomes clear, you will need to weigh the trade- offs between that value and the pain of breaking your developers or customers.

这是“可用”和“正确”之间区别的一个非常基本的例子。对于一个短期的程序,依赖容器的迭代顺序不会导致任何技术问题。另一方面,对于一个软件工程项目来说,如果有足够的时间,这种对已定义顺序的依赖是一种风险使更改迭代顺序变得有价值。这种价值可以通过多种方式体现出来,无论是效率、安全性,还是仅仅是数据结构的未来验证,以允许将来的更改。当这一价值变得清晰时,你需要权衡这一价值与破坏开发人员或客户的痛苦之间的平衡。

10A type of Denial-of-Service (DoS) attack in which an untrusted user knows the structure of a hash table and the hash function and provides data in such a way as to degrade the algorithmic performance of operations on the table.

一种拒绝服务(DoS)攻击,其中不受信任的用户知道哈希表和哈希函数的结构,并以降低表上操作的算法性能的方式提供数据。

Some languages specifically randomize hash ordering between library versions or even between execution of the same program in an attempt to prevent dependencies. But even this still allows for some Hyrum’s Law surprises: there is code that uses hash iteration ordering as an inefficient random-number generator. Removing such randomness now would break those users. Just as entropy increases in every thermodynamic system, Hyrum’s Law applies to every observable behavior.

一些语言专门在库版本之间,甚至在执行相同程序的随机散列排序,以防止依赖关系。但即使这样,也会出现一些令人惊讶的海勒姆定律:有些代码使用散列迭代排序作为一个低效的随机数生成器。现在消除这种随机性将破坏这些用户原使用方式。正如熵在每个热力学系统中增加一样,海勒姆定律适用于所有可观察到的行为。

Thinking over the differences between code written with a “works now” and a “works indefinitely” mentality, we can extract some clear relationships. Looking at code as an artifact with a (highly) variable lifetime requirement, we can begin to categorize programming styles: code that depends on brittle and unpublished features of its dependencies is likely to be described as “hacky” or “clever,” whereas code that follows best practices and has planned for the future is more likely to be described as “clean” and “maintainable.” Both have their purposes, but which one you select depends crucially on the expected life span of the code in question. We’ve taken to saying, “It’s programming if ‘clever’ is a compliment, but it’s software engineering if ‘clever’ is an accusation.”

思考一下用“当前可用”和“一直可用”心态编写的代码之间的差异,我们可以提取出一些明确的关系。将代码视为具有(高度)可变生命周期需求的构件,我们可以开始对编程风格进行分类:依赖其依赖性的脆弱和未发布特性的代码可能被描述为“黑客”或“聪明”而遵循最佳实践并为未来规划的代码更可能被描述为“干净”和“可维护”。两者都有其目的,但你选择哪一个关键取决于所讨论代码的预期生命周期。我们常说,“如果‘聪明’是一种恭维,那就是程序,如果‘聪明’是一种指责,那就是软件工程。”

Why Not Just Aim for “Nothing Changes”? 为什么不以“无变化”为目标?

Implicit in all of this discussion of time and the need to react to change is the assumption that change might be necessary. Is it?

在所有关于时间和对变化作出反应的讨论中,隐含着一个假设,即变化可能是必要的?

As with effectively everything else in this book, it depends. We’ll readily commit to “For most projects, over a long enough time period, everything underneath them might need to be changed.” If you have a project written in pure C with no external dependencies (or only external dependencies that promise great long-term stability, like POSIX), you might well be able to avoid any form of refactoring or difficult upgrade. C does a great job of providing stability—in many respects, that is its primary purpose.

与本书中的其他内容一样,这取决于实际情况。我们很乐意承诺“对于大多数项目,在足够长的时间内,它们下面的一切都可能需要更改。”如果你有一个用纯C编写的项目,没有外部依赖项(或者只有保证长期稳定性的外部依赖项,如POSIX),你完全可以避免任何形式的重构或困难的升级。C在提供多方面稳定性方面做了大量工作,这是其首要任务。

Most projects have far more exposure to shifting underlying technology. Most programming languages and runtimes change much more than C does. Even libraries implemented in pure C might change to support new features, which can affect downstream users. Security problems are disclosed in all manner of technology, from processors to networking libraries to application code. Every piece of technology upon which your project depends has some (hopefully small) risk of containing critical bugs and security vulnerabilities that might come to light only after you’ve started relying on it. If you are incapable of deploying a patch for Heartbleed or mitigating speculative execution problems like Meltdown and Spectre because you’ve assumed (or promised) that nothing will ever change, that is a significant gamble.

大多数项目更多地接触到不断变化的基础技术。大多数编程语言和运行时的变化要比C大得多。甚至用纯C实现的库也可能改变以支持新特性,这可能会影响下游用户。从处理器到网络库,再到应用程序代码,各种技术都会暴露安全问题。你的项目所依赖的每一项技术都有一些(希望很小)包含关键bug和安全漏洞的风险,这些漏洞只有在你开始依赖它之后才会暴露出来。如果你无法部署心脏出血或缓解推测性执行漏洞(如熔毁和幽灵)的修补程序,因为你假设(或保证)什么都不会改变,这是一场巨大的赌博。

Efficiency improvements further complicate the picture. We want to outfit our datacenters with cost-effective computing equipment, especially enhancing CPU efficiency. However, algorithms and data structures from early-day Google are simply less efficient on modern equipment: a linked-list or a binary search tree will still work fine, but the ever-widening gap between CPU cycles versus memory latency impacts what “efficient” code looks like. Over time, the value in upgrading to newer hardware can be diminished without accompanying design changes to the software. Backward compatibility ensures that older systems still function, but that is no guarantee that old optimizations are still helpful. Being unwilling or unable to take advantage of such opportunities risks incurring large costs. Efficiency concerns like this are particularly subtle: the original design might have been perfectly logical and following reasonable best practices. It’s only after an evolution of backward-compatible changes that a new, more efficient option becomes important. No mistakes were made, but the passage of time still made change valuable.

效率的提高使情况更加复杂。我们希望为数据中心配备经济高效的计算设备,特别是提高CPU效率。然而,早期谷歌的算法和数据结构在现代设备上效率较低:链表或二叉搜索树仍能正常工作,但CPU周期与内存延迟之间的差距不断扩大,影响了看起来还像“高效”代码。随着时间的推移,升级到较新硬件的价值会降低,而无需对软件进行相应的设计更改。向后兼容性确保了旧系统仍能正常工作,但这并不能保证旧的优化仍然有用。不愿意或无法利用这些机会可能会带来巨大的成本。像这样的效率问题尤其微妙:最初的设计可能完全符合逻辑,并遵循合理的最佳实践。只有在向后兼容的变化演变之后,新的、更有效的选择才变得重要。虽然没有犯错误,但随着时间的推移,变化仍然是有价值的。

Concerns like those just mentioned are why there are large risks for long-term projects that haven’t invested in sustainability. We must be capable of responding to these sorts of issues and taking advantage of these opportunities, regardless of whether they directly affect us or manifest in only the transitive closure of technology we build upon. Change is not inherently good. We shouldn’t change just for the sake of change. But we do need to be capable of change. If we allow for that eventual necessity, we should also consider whether to invest in making that capability cheap. As every system administrator knows, it’s one thing to know in theory that you can recover from tape, and another to know in practice exactly how to do it and how much it will cost when it becomes necessary. Practice and expertise are great drivers of efficiency and reliability.

像刚才提到的那些担忧,没有对可持续性的长期项目进行投入是存在巨大风险。我们必须能够应对这些问题,并利用好机会,无论它们是否直接影响我们,或者仅仅表现为我们所建立的技术的过渡性封闭中。变化本质上不是好事。我们不应该仅仅为了改变而改变。但我们确实需要有能力改变。如果我们考虑到最终的必要性,我们也应该考虑是否加大投入使这种能力变得简单易用(成本更低)。正如每个系统管理员都知道的那样,从理论上知道你可以从磁带恢复是一回事,在实践中确切地知道如何进行恢复以及在必要时需要花费多少钱是另一回事。实践和专业知识是效率和可靠性的重要驱动力。

Scale and Efficiency 规模和效率

As noted in the Site Reliability Engineering (SRE) book,11 Google’s production system as a whole is among the most complex machines created by humankind. The complexity involved in building such a machine and keeping it running smoothly has required countless hours of thought, discussion, and redesign from experts across our organization and around the globe. So, we have already written a book about the complexity of keeping that machine running at that scale.

正如(SRE)这本书所指出的,谷歌的生产系统作为一个整体是人类创造的最复杂的系统之一。构建这样复杂系统并保持其平稳运行所涉及的复杂性需要我们组织和全球各地的专家进行无数小时的思考、讨论和重构。因此,我们已经写了一本书,讲述了保持机器以这种规模运行的复杂性。

Much of this book focuses on the complexity of scale of the organization that produces such a machine, and the processes that we use to keep that machine running over time. Consider again the concept of codebase sustainability: “Your organization’s codebase is sustainable when you are able to change all of the things that you ought to change, safely, and can do so for the life of your codebase.” Hidden in the discussion of capability is also one of costs: if changing something comes at inordinate cost, it will likely be deferred. If costs grow superlinearly over time, the operation clearly is not scalable.12 Eventually, time will take hold and something unexpected will arise that you absolutely must change. When your project doubles in scope and you need to perform that task again, will it be twice as labor intensive? Will you even have the human resources required to address the issue next time?

本书的大部分内容都集中在产生这种系统的组织规模的复杂性,以及我们用来保持系统长期运行的过程。再考虑代码库可持续性的概念:“当你能够安全地改变你应该改变的所有事情,你的组织的代码库是可持续的,并且可以为你的代码库的生命做这样的事情。”隐藏在能力的讨论中也是成本的一个方面:如果改变某事的代价太大,它可能会被推迟。如果成本随着时间的推移呈超线性增长,运营显然是不可扩展的。最终,时间会占据主导地位,出现一些意想不到的情况,你必须改变。当你的项目范围扩大了一倍,并且你需要再次执行该任务时,它会是劳动密集型的两倍吗?下次你是否有足够的人力资源来解决这个问题?

Human costs are not the only finite resource that needs to scale. Just as software itself needs to scale well with traditional resources such as compute, memory, storage, and bandwidth, the development of that software also needs to scale, both in terms of human time involvement and the compute resources that power your development workflow. If the compute cost for your test cluster grows superlinearly, consuming more compute resources per person each quarter, you’re on an unsustainable path and need to make changes soon.

人力成本不是唯一需要扩大规模的有限资源。就像软件本身需要与传统资源(如计算、内存、存储和带宽)进行良好的可扩展一样,软件的开发也需要进行扩展,包括人力时间的参与和支持开发工作流程的计算资源。如果测试集群的计算成本呈超线性增长,每个季度人均消耗更多的计算资源,那么你的项目就走上了一条不可持续的道路,需要尽快做出改变。

Finally, the most precious asset of a software organization—the codebase itself—also needs to scale. If your build system or version control system scales superlinearly over time, perhaps as a result of growth and increasing changelog history, a point might come at which you simply cannot proceed. Many questions, such as “How long does it take to do a full build?”, “How long does it take to pull a fresh copy of the repository?”, or “How much will it cost to upgrade to a new language version?” aren’t actively monitored and change at a slow pace. They can easily become like the metaphorical boiled frog; it is far too easy for problems to worsen slowly and never manifest as a singular moment of crisis. Only with an organization-wide awareness and commitment to scaling are you likely to keep on top of these issues.

最后,软件系统最宝贵的资产代码库本身也需要扩展。如果你的构建系统或版本控制系统随着时间的推移呈超线性扩展,也许是由于内容增长和不断增加的变更日志历史,那么可能会出现无法持续的情况。许多问题,如“完成完整构建需要多长时间?”、“拉一个新的版本库需要多长时间?”或“升级到新语言版本需要多少成本?”都没有受到有效的监管,并且效率变得缓慢。这些问题很容易地变得像温水煮青蛙;问题很容易慢慢恶化,而不会表现为单一的危机时刻。只有在整个组织范围内提高意识并致力于扩大规模,才可能保持对这些问题的关注。

Everything your organization relies upon to produce and maintain code should be scalable in terms of overall cost and resource consumption. In particular, everything your organization must do repeatedly should be scalable in terms of human effort. Many common policies don’t seem to be scalable in this sense.

你的组织生产和维护代码所依赖的一切都应该在总体成本和资源消耗方面具有可扩展性。特别是,你的组织必须重复做的每件事都应该在人力方面具有可扩展性。从这个意义上讲,许多通用策略似乎不具有可扩展性。

11Beyer, B. et al. Site Reliability Engineering: How Google Runs Production Systems. (Boston: O’Reilly Media,2016).

Beyer, B. et al. Site Reliability Engineering: 谷歌如何运行生产系统。(Boston: O'Reilly Media, 2016).

12Whenever we use “scalable” in an informal context in this chapter, we mean “sublinear scaling with regard to human interactions.”

在本章中,当我们在非正式语境中使用“可扩展性”时,我们的意思是“在人类交互的次线性伸缩性”

Policies That Don’t Scale 不可扩展的策略

With a little practice, it becomes easier to spot policies with bad scaling properties. Most commonly, these can be identified by considering the work imposed on a single engineer and imagining the organization scaling up by 10 or 100 times. When we are 10 times larger, will we add 10 times more work with which our sample engineer needs to keep up? Does the amount of work our engineer must perform grow as a function of the size of the organization? Does the work scale up with the size of the codebase? If either of these are true, do we have any mechanisms in place to automate or optimize that work? If not, we have scaling problems.

只要稍加练习,就可以更容易地发现具有不可扩展的策略。最常见的情况是,可以通过考虑施加在单个设计并想象组织规模扩大10倍或100倍。当我们的规模增大10倍时,我们会增加10倍的工作量,而我们的工程师能跟得上吗?我们的工程师的工作量是否随着组织的规模而增长?工作是否随着代码库的大小而变多?如果这两种情况都是真实的,我们是否有机制来自动化或优化这项工作?如果没有,我们就有扩展问题。

Consider a traditional approach to deprecation. We discuss deprecation much more in Chapter 15, but the common approach to deprecation serves as a great example of scaling problems. A new Widget has been developed. The decision is made that everyone should use the new one and stop using the old one. To motivate this, project leads say “We’ll delete the old Widget on August 15th; make sure you’ve converted to the new Widget.”

考虑传统的弃用方式。我们在第15章中详细讨论了弃用,但常用的弃用方法是扩展问题的一个很好的例子。开发了一个新的小组件。决定是每个人都应该使用新的,停止使用旧的。为了激发这一点,项目负责人说:“我们将在8月15日删除旧的小组件;确保你已转换为新的小组件。”

This type of approach might work in a small software setting but quickly fails as both the depth and breadth of the dependency graph increases. Teams depend on an ever- increasing number of Widgets, and a single build break can affect a growing percentage of the company. Solving these problems in a scalable way means changing the way we do deprecation: instead of pushing migration work to customers, teams can internalize it themselves, with all the economies of scale that provides.

这种方法可能适用于小型软件项目,但随着依赖关系图的深度和广度的增加,很快就会失败。团队依赖越来越多的小部件,单个构建中断可能会影响公司不断增长的百分比。以一种可扩展的方式解决这些问题,意味着需要改变我们废弃的方式: 不是将迁移工作推给客户,团队可以将其内部消化,并提供所需资源投入。

In 2012, we tried to put a stop to this with rules mitigating churn: infrastructure teams must do the work to move their internal users to new versions themselves or do the update in place, in backward-compatible fashion. This policy, which we’ve called the “Churn Rule,” scales better: dependent projects are no longer spending progressively greater effort just to keep up. We’ve also learned that having a dedicated group of experts execute the change scales better than asking for more maintenance effort from every user: experts spend some time learning the whole problem in depth and then apply that expertise to every subproblem. Forcing users to respond to churn means that every affected team does a worse job ramping up, solves their immediate problem, and then throws away that now-useless knowledge. Expertise scales better.

2012年,我们试图通过降低流失规则来阻止这种情况:基础架构团队必须将内部用户迁移到新版本,或者以向后兼容的方式进行更新。我们称之为“流失规则”的这一策略具有更好的扩展性:依赖项目不再为了跟上进度而花费更多的精力。我们还了解到,有一个专门的专家组来执行变更规模比要求每个用户付出更多的维护工作要好:专家们花一些时间深入学习整个问题,然后将专业知识应用到每个子问题上。迫使用户对流失作出反应意味着每个受影响的团队做了更糟糕的工作,解决了他们眼前的问题,然后扔掉了那些对现在无效的知识。专业知识的扩展性更好。

The traditional use of development branches is another example of policy that has built-in scaling problems. An organization might identify that merging large features into trunk has destabilized the product and conclude, “We need tighter controls on when things merge. We should merge less frequently.” This leads quickly to every team or every feature having separate dev branches. Whenever any branch is decided to be “complete,” it is tested and merged into trunk, triggering some potentially expensive work for other engineers still working on their dev branch, in the form of resyncing and testing. Such branch management can be made to work for a small organization juggling 5 to 10 such branches. As the size of an organization (and the number of branches) increases, it quickly becomes apparent that we’re paying an ever-increasing amount of overhead to do the same task. We’ll need a different approach as we scale up, and we discuss that in Chapter 16.

传统的开发分支的使用是另一个有内在扩展问题的例子。一个组织可能会发现,将大的功能分支合并到主干中会破坏产品的稳定性,并得出结论:“我们需要对分支的合并时间进行控制,还要降低合并的频率”。这很快会导致每个团队或每个功能都有单独的开发分支。每当任何分支被确定为“完整”时,都会对其进行测试并合并到主干中,从而引发其他仍在开发分支上工作的工程师以重新同步和测试,造成巨大的工作量。这样的分支机构管理模式可以应用在小型组织里,管理5到10个这样的分支机构。随着一个组织的规模(以及分支机构的数量)的增加,我们很快就会发现,为了完成同样的任务,我们付出越来越多的管理成本。随着规模的扩大,我们需要一种不同的方法,我们将在第16章中对此进行讨论。

Policies That Scale Well 规模化策略

What sorts of policies result in better costs as the organization grows? Or, better still, what sorts of policies can we put in place that provide superlinear value as the organization grows?

随着公司的发展,什么样的策略会带来更低的成本?或者,最好是,随着组织化的发展,我们可以制定什么样的策略来提供超高的价值?

One of our favorite internal policies is a great enabler of infrastructure teams, protecting their ability to make infrastructure changes safely. “If a product experiences outages or other problems as a result of infrastructure changes, but the issue wasn’t surfaced by tests in our Continuous Integration (CI) system, it is not the fault of the infrastructure change.” More colloquially, this is phrased as “If you liked it, you should have put a CI test on it,” which we call “The Beyoncé Rule.”13 From a scaling perspective, the Beyoncé Rule implies that complicated, one-off bespoke tests that aren’t triggered by our common CI system do not count. Without this, an engineer on an infrastructure team could conceivably need to track down every team with any affected code and ask them how to run their tests. We could do that when there were a hundred engineers. We definitely cannot afford to do that anymore.

我们最喜欢的内部策略之一是为基础架构团队提供强大的支持,维护他们安全地进行基础措施更改的能力。“如果一个产品由于基础架构更改而出现停机或其他问题,但我们的持续集成(CI)系统中的测试没有发现问题,这不是基础架构变更的错。”更通俗地说,这是“如果你喜欢它,你应该对它进行CI测试”,我们称之为“碧昂斯规则。”从可伸缩性的角度来看,碧昂斯规则意味着复杂的、一次性的定制测试(不是由我们的通用CI系统触发的)不算数。如果没有这一点,基础架构团队的工程师需要跟踪每个有任何受影响代码的团队,问他们如何进行测试。当有一百个工程师的时候,我们可以这样做。我们绝对不能这样做。

We’ve found that expertise and shared communication forums offer great value as an organization scales. As engineers discuss and answer questions in shared forums, knowledge tends to spread. New experts grow. If you have a hundred engineers writing Java, a single friendly and helpful Java expert willing to answer questions will soon produce a hundred engineers writing better Java code. Knowledge is viral, experts are carriers, and there’s a lot to be said for the value of clearing away the common stumbling blocks for your engineers. We cover this in greater detail in Chapter 3.

我们发现,随着组织规模的扩大,专业知识和共享交流论坛提供了巨大的价值。随着工程师在共享论坛中讨论和回答问题,知识往往会传播。新的专家人数不断增加。如果你有100名工程师编写Java,那么一位愿意回答问题的友好且乐于助人的Java专家很快就会产生一个数百名工程师编写更好的Java代码。知识是病毒,专家是载体,扫除工程师常见的绊脚石是非常有价值的。我们将在第3章更详细地介绍这一点。

13This is a reference to the popular song “Single Ladies,” which includes the refrain “If you liked it then you shoulda put a ring on it.”

这是指流行歌曲《单身女士》,其中包括 "如果你喜欢它,你就应该给它戴上戒指。

Example: Compiler Upgrade 示例:编译器升级

Consider the daunting task of upgrading your compiler. Theoretically, a compiler upgrade should be cheap given how much effort languages take to be backward compatible, but how cheap of an operation is it in practice? If you’ve never done such an upgrade before, how would you evaluate whether your codebase is compatible with that change?

考虑升级编译器的艰巨任务。从理论上讲,编译器的升级应该是简单的,因为语言需要多少工作才能向后兼容,但是在实际操作中又有多简单呢?如果你以前从未做过这样的升级,你将如何评价你的代码库是否与兼容升级?

In our experience, language and compiler upgrades are subtle and difficult tasks even when they are broadly expected to be backward compatible. A compiler upgrade will almost always result in minor changes to behavior: fixing miscompilations, tweaking optimizations, or potentially changing the results of anything that was previously undefined. How would you evaluate the correctness of your entire codebase against all of these potential outcomes?

根据我们的经验,语言和编译器升级是微妙而困难的任务,即使人们普遍认为它们是向后兼容的。编译器升级几乎总是会导致编译的微小变化:修复错误编译、调整优化,或者潜在地改变任何以前未定义的结果。你将如何针对所有这些潜在的结果来评估你整个代码库的正确性?

The most storied compiler upgrade in Google’s history took place all the way back in 2006. At that point, we had been operating for a few years and had several thousand engineers on staff. We hadn’t updated compilers in about five years. Most of our engineers had no experience with a compiler change. Most of our code had been exposed to only a single compiler version. It was a difficult and painful task for a team of (mostly) volunteers, which eventually became a matter of finding shortcuts and simplifications in order to work around upstream compiler and language changes that we didn’t know how to adopt.14 In the end, the 2006 compiler upgrade was extremely painful. Many Hyrum’s Law problems, big and small, had crept into the codebase and served to deepen our dependency on a particular compiler version. Breaking those implicit dependencies was painful. The engineers in question were taking a risk: we didn’t have the Beyoncé Rule yet, nor did we have a pervasive CI system, so it was difficult to know the impact of the change ahead of time or be sure they wouldn’t be blamed for regressions.

谷歌历史上最具传奇色彩的编译器升级发生在2006年。当时,我们已经运行了几年,拥有数千名工程师。我们大约有五年没有升级过编译器。我们的大多数工程师都没有升级编译器的经验。我们的大部分代码只针对在单一编译器版本。对于一个由(大部分)志愿者组成的团队来说,这是一项艰难而痛苦的任务,最终变成了寻找捷径和简化的问题,以便绕过我们不知道如何采用的上游编译器和语言变化。最后,2006年的编译器升级过程非常痛苦。许多海勒姆定律问题,无论大小,都潜入了代码库,加深了我们对特定编译器版本的依赖。打破这些隐式依赖性是痛苦的。相关工程师正在冒风险:我们还没有碧昂斯规则,也没有通用的CI系统,因此很难提前知道更改的影响,或者确保他们不会因回退而受到指责。

This story isn’t at all unusual. Engineers at many companies can tell a similar story about a painful upgrade. What is unusual is that we recognized after the fact that the task had been painful and began focusing on technology and organizational changes to overcome the scaling problems and turn scale to our advantage: automation (so that a single human can do more), consolidation/consistency (so that low-level changes have a limited problem scope), and expertise (so that a few humans can do more).

这个故事一点也不稀奇。许多公司的工程师都可以讲述一个关于痛苦升级的故事。不同的是,我们在经历了痛苦的任务之后认识到了这一点,并开始关注技术和组织变革,以克服规模问题,并将规模转变为我们的优势:自动化(这样一个人就可以做到更多)、整合/一致性(这样低级别的更改影响有限的问题范围)和专业知识(以便少数人就可以做得更多)。

The more frequently you change your infrastructure, the easier it becomes to do so. We have found that most of the time, when code is updated as part of something like a compiler upgrade, it becomes less brittle and easier to upgrade in the future. In an ecosystem in which most code has gone through several upgrades, it stops depending on the nuances of the underlying implementation; instead, it depends on the actual abstraction guaranteed by the language or OS. Regardless of what exactly you are upgrading, expect the first upgrade for a codebase to be significantly more expensive than later upgrades, even controlling for other factors.

你更改基础设施的频率越高,更改就越容易。我们发现,在大多数情况下,当代码作为编译器升级的一部分进行更新时,它会变得没那么脆弱,将来更容易升级。大多数代码都经历了几次升级的一个系统中,它的停止取决于底层实现的细微差别。相反,它取决于语言或操作系统所保证的抽象。无论你升级的是什么,代码库的第一次升级都比以后的升级要复杂得多,甚至可以控制其他因素。

14Specifically, interfaces from the C++ standard library needed to be referred to in namespace std, and an optimization change for std::string turned out to be a significant pessimization for our usage, thus requiring some additional workarounds.

具体来说,来自C++标准库的接口需要在命名空间std中被引用,而针对std::string的优化改变对我们的使用来说是一个重大的减值,因此需要一些额外的解决方法。

Through this and other experiences, we’ve discovered many factors that affect the flexibility of a codebase:

- Expertise

We know how to do this; for some languages, we’ve now done hundreds of compiler upgrades across many platforms. - Stability

There is less change between releases because we adopt releases more regularly; for some languages, we’re now deploying compiler upgrades every week or two. - Conformity

There is less code that hasn’t been through an upgrade already, again because we are upgrading regularly. - Familiarity

Because we do this regularly enough, we can spot redundancies in the process of performing an upgrade and attempt to automate. This overlaps significantly with SRE views on toil.15 - Policy

We have processes and policies like the Beyoncé Rule. The net effect of these processes is that upgrades remain feasible because infrastructure teams do not need to worry about every unknown usage, only the ones that are visible in our CI systems.

通过这些和其他经验,我们发现了许多影响代码库灵活性的因素:

- 专业知识 我们知道如何做到这一点;对于某些语言,我们现在已经在许多平台上进行了数百次编译器升级。

- 稳定性

版本之间的更改更少,因为我们更有规律的采用版本;对于某些语言,我们现在每一到两周进行一次编译器升级部署。 - 一致性

没有经过升级的代码更少了,这也是因为我们正在定期升级。 - 熟悉

因为我们经常这样做,所以我们可以在执行升级的过程中发现冗余并尝试自动化。这是与SRE观点一致的地方。 - 策略

我们有类似碧昂斯规则的流程和策略。这些程序的净效果是,升级仍然是可行的,因为基础设施团队不需要担心每一个未知的使用,只需要担心我们的CI系统中常规的使用。

The underlying lesson is not about the frequency or difficulty of compiler upgrades, but that as soon as we became aware that compiler upgrade tasks were necessary, we found ways to make sure to perform those tasks with a constant number of engineers, even as the codebase grew.16 If we had instead decided that the task was too expensive and should be avoided in the future, we might still be using a decade-old compiler version. We would be paying perhaps 25% extra for computational resources as a result of missed optimization opportunities. Our central infrastructure could be vulnerable to significant security risks given that a 2006-era compiler is certainly not helping to mitigate speculative execution vulnerabilities. Stagnation is an option, but often not a wise one.

潜在的教训不是关于编译器升级的频率或难度,而是一旦我们意识到编译器升级任务是必要的,我们就找到了方法,确保在代码库增长的情况下,由固定数量的工程师执行这些任务。如果我们认为任务成本太高,应该学会避免,我们可以仍然使用十年前的编译器版本。由于错过了优化机会,我们需要额外支付25%的计算资源。考虑到2006年的编译器对缓解推测性执行漏洞没有效果,我们的中央基础设施可能会面临重大的安全风险,这不是一个明智的选择。

15Beyer et al. Site Reliability Engineering: How Google Runs Production Systems, Chapter 5, “Eliminating Toil.”

Beyer等人,《SRE:Google运维解密》,第五章 减少琐事。

16In our experience, an average software engineer (SWE) produces a pretty constant number of lines of code per unit time. For a fixed SWE population, a codebase grows linearly—proportional to the count of SWE- months over time. If your tasks require effort that scales with lines of code, that’s concerning.

根据我们的经验,平均软件工程师(SWE)每单位时间产生相当恒定的代码行数。对于固定的SWE总体,随着时间的推移,代码库的增长与SWE月数成线性比例。如果您的任务所需的工作量与代码行数成正比,那就令人担忧了。

Shifting Left 左移

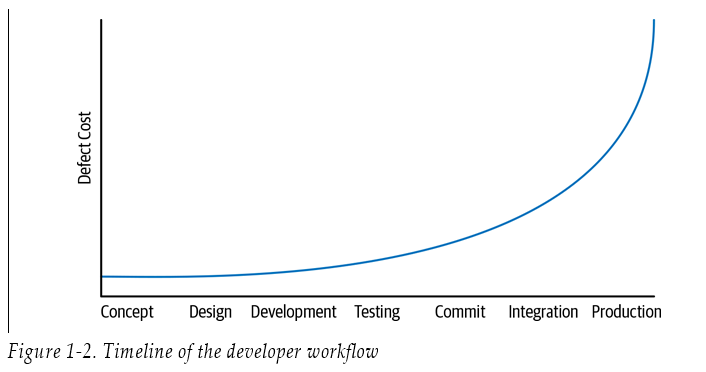

One of the broad truths we’ve seen to be true is the idea that finding problems earlier in the developer workflow usually reduces costs. Consider a timeline of the developer workflow for a feature that progresses from left to right, starting from conception and design, progressing through implementation, review, testing, commit, canary, and eventual production deployment. Shifting problem detection to the “left” earlier on this timeline makes it cheaper to fix than waiting longer, as shown in Figure 1-2.

我们发现,在开发人员工作流程的早期发现问题通常可以降低成本,这是一个普遍的真理。考虑一下开发人员工作流程的时间轴,该时间轴从左到右依次为:从构思和设计开始,经过实施、审核、测试、提交、金丝雀和最终的生产部署。如图 1-2 所示,在此时间轴上将问题检测提前到 "左侧",解决问题的成本会比等待时间更长。

This term seems to have originated from arguments that security mustn’t be deferred until the end of the development process, with requisite calls to “shift left on security.” The argument in this case is relatively simple: if a security problem is discovered only after your product has gone to production, you have a very expensive problem. If it is caught before deploying to production, it may still take a lot of work to identify and remedy the problem, but it’s cheaper. If you can catch it before the original developer commits the flaw to version control, it’s even cheaper: they already have an understanding of the feature; revising according to new security constraints is cheaper than committing and forcing someone else to triage it and fix it.

这个术语似乎源一种观点,即安全问题不能推迟到开发过程的最后阶段,必须要求“在安全上向左转移”。这种情况下的论点相对简单:如果安全问题是在产品投入生产后才发现的,修复的成本就非常高。如果在部署到生产之前就发现了安全问题,那也需要花费大量的工作来检测和修复问题,但成本更低些。如果你能够在最初的开发之前发现安全问题,将缺陷提交到版本控制就被发现,修复的成本更低:他们已经了解该功能;根据新的安全约束规范进行开发,要比提交代码后再让其他人分类标识并修复它更简单。

The same basic pattern emerges many times in this book. Bugs that are caught by static analysis and code review before they are committed are much cheaper than bugs that make it to production. Providing tools and practices that highlight quality, reliability, and security early in the development process is a common goal for many of our infrastructure teams. No single process or tool needs to be perfect, so we can assume a defense-in-depth approach, hopefully catching as many defects on the left side of the graph as possible.

同样的基本模式在本书中多次出现。在提交之前通过静态分析和代码审查发现的bug要比投入生产的bug成本更低。在开发过程的早期提供高质量、可靠性和安全性的工具和实践是我们许多基础架构团队的共同目标。没有一个过程或工具是完美的,所以我们可以采取纵深防御的方法,希望尽早抓住图表左侧的缺陷。

Trade-offs and Costs 权衡和成本

If we understand how to program, understand the lifetime of the software we’re maintaining, and understand how to maintain it as we scale up with more engineers producing and maintaining new features, all that is left is to make good decisions. This seems obvious: in software engineering, as in life, good choices lead to good outcomes. However, the ramifications of this observation are easily overlooked. Within Google, there is a strong distaste for “because I said so.” It is important for there to be a decider for any topic and clear escalation paths when decisions seem to be wrong, but the goal is consensus, not unanimity. It’s fine and expected to see some instances of “I don’t agree with your metrics/valuation, but I see how you can come to that conclusion.” Inherent in all of this is the idea that there needs to be a reason for everything; “just because,” “because I said so,” or “because everyone else does it this way” are places where bad decisions lurk. Whenever it is efficient to do so, we should be able to explain our work when deciding between the general costs for two engineering options.

如果我们了解如何编程,了解我们所维护的软件的生命周期,并且随着在我们随着更多的工程师一起开发和维护新功能,了解扩大规模时如何运维它,那么剩下的就是做出正确的决策。这是显而易见的:在软件工程中,如同生活一样,好的选择会带来好的结果。然而,这一观点很容易被忽视。在谷歌内部,人们对“因为我这么说了”有反对的意见。重要的是,任何议题都要有一个决策者,当决策是错误的时候,要有明确的改进路径,但目标是共识,而不是一致。看到一些 "我不同意你的衡量标准/评价,但我知道你是如何得出这个结论的 "的情况是没有问题的,也是可以预期的。所有这一切的内在想法是,每件事都需要一个理由;“仅仅因为”、“因为我这么说”或“因为其他人都这样做”是潜在错误的决策。 只要这样做是有效的,在决定两个工程方案的一般成本时,我们应该能够解释清楚。

What do we mean by cost? We are not only talking about dollars here. “Cost” roughly translates to effort and can involve any or all of these factors:

- Financial costs (e.g., money)

- Resource costs (e.g., CPU time)

- Personnel costs (e.g., engineering effort)

- Transaction costs (e.g., what does it cost to take action?)

- Opportunity costs (e.g., what does it cost to not take action?)

- Societal costs (e.g., what impact will this choice have on society at large?)

我们所说的成本是什么呢?我们这里不仅仅是指金钱。“成本”大致可以转化为努力的方向,可以包括以下任何或所有因素:

- 财务成本(如金钱)

- 资源成本(如CPU时间)

- 人员成本(例如,工作量)

- 交易成本(例如,采取行动的成本是多少?)

- 机会成本(例如,不采取行动的成本是多少?)

- 社会成本(例如,这个选择将对整个社会产生什么影响?)

Historically, it’s been particularly easy to ignore the question of societal costs. However, Google and other large tech companies can now credibly deploy products with billions of users. In many cases, these products are a clear net benefit, but when we’re operating at such a scale, even small discrepancies in usability, accessibility, fairness, or potential for abuse are magnified, often to the detriment of groups that are already marginalized. Software pervades so many aspects of society and culture; therefore, it is wise for us to be aware of both the good and the bad that we enable when making product and technical decisions. We discuss this much more in Chapter 4.

从历史上看,忽视社会成本的问题尤其容易出现。然而,谷歌和其他大型科技公司现在可以可靠地部署拥有数十亿用户的产品。在许多情况下,这些产品是高净效益的,但当我们以这样的规模运营时,即使在可用性、可访问性和公平性方面或潜在的滥用方面的微小差异也会被放大,往往对边缘化的群体产生不利影响。软件渗透到社会和文化的各个方面;因此,明智的做法是,在做出产品和技术决策时,我们要意识到我们所能带来的好处和坏处。我们将在第4章对此进行更多讨论。

In addition to the aforementioned costs (or our estimate of them), there are biases: status quo bias, loss aversion, and others. When we evaluate cost, we need to keep all of the previously listed costs in mind: the health of an organization isn’t just whether there is money in the bank, it’s also whether its members are feeling valued and productive. In highly creative and lucrative fields like software engineering, financial cost is usually not the limiting factor—personnel cost usually is. Efficiency gains from keeping engineers happy, focused, and engaged can easily dominate other factors, simply because focus and productivity are so variable, and a 10-to-20% difference is easy to imagine.

除了上述的成本(或我们对其的估计),还有一些偏差:维持现状偏差(个体在决策时,倾向于不作为、维持当前的或者以前的决策的一种现象。这一定义揭示个体在决策时偏好事件当前的状态,而且不愿意采取行动来改变这一状态,当面对一系列决策选项时,倾向于选择现状选项),损失厌恶偏差(人们面对同样的损失和收益时感到损失对情绪影响更大)等。当我们评估成本时,我们需要牢记之前列出的所有成本:一个组织的健康不仅仅是银行里是否有钱,还包括其成员是否感到有价值和有成就感。在软件等高度创新和利润丰厚的领域在工程设计中,财务成本通常不是限制因素,而人力资源是。保持工程师的快乐、专注和参与所带来的效率提升会成为主导因素,仅仅是因为专注力和生产力变化大,会有10-20%的差异很容易想象。

Example: Markers 示例:记号笔

In many organizations, whiteboard markers are treated as precious goods. They are tightly controlled and always in short supply. Invariably, half of the markers at any given whiteboard are dry and unusable. How often have you been in a meeting that was disrupted by lack of a working marker? How often have you had your train of thought derailed by a marker running out? How often have all the markers just gone missing, presumably because some other team ran out of markers and had to abscond with yours? All for a product that costs less than a dollar.

在许多组织中,白板记号笔被视为贵重物品。它们受到严格的控制,而且总是供不应求。在任何的白板上,都有一半的记号笔是干的,无法使用。你有多少次因为没有一个好用的记号笔而中断会议进程?多少次因为记号笔水用完而导致思路中断?又有多少次,所有的记号笔都不翼而飞,大概是因为其他团队的记号笔用完了,不得不拿走你的记号笔?所有这些都是因为一个价格不到一美元的产品。

Google tends to have unlocked closets full of office supplies, including whiteboard markers, in most work areas. With a moment’s notice it is easy to grab dozens of markers in a variety of colors. Somewhere along the line we made an explicit trade- off: it is far more important to optimize for obstacle-free brainstorming than to protect against someone wandering off with a bunch of markers.

谷歌往往在大多数工作区域都有未上锁的柜子,里面装满了办公用品,包括记号笔。只要稍加注意,就可以很容易地拿到各种颜色的几十支记号笔。在某种程度上,我们做了一个明确的权衡:优化无障碍头脑风暴要比防止有人拿着一堆记号笔走神重要得多。

We aim to have the same level of eyes-open and explicit weighing of the cost/benefit trade-offs involved for everything we do, from office supplies and employee perks through day-to-day experience for developers to how to provision and run global- scale services. We often say, “Google is a data-driven culture.” In fact, that’s a simplification: even when there isn’t data, there might still be evidence, precedent, and argument. Making good engineering decisions is all about weighing all of the available inputs and making informed decisions about the trade-offs. Sometimes, those decisions are based on instinct or accepted best practice, but only after we have exhausted approaches that try to measure or estimate the true underlying costs.

我们的目标是对我们所做的每件事都有同样程度的关注和明确的成本/收益权衡,从办公用品和员工津贴到开发者的日常体验,再到如何提供和运行全球规模的服务。我们经常说,“谷歌是一家数据驱动的公司。”事实上,这很简单:即使没有数据,也会有证据、先例和论据。做出好的工程决策就是权衡所有可用的输入,并就权衡做出明智的决策。有时,这些决策是基于本能或公认的最佳实践,但仅是一种假设之后,我们用尽了各种方法来衡量或估计真正的潜在成本。

In the end, decisions in an engineering group should come down to very few things:

- We are doing this because we must (legal requirements, customer requirements).

- We are doing this because it is the best option (as determined by some appropriate decider) we can see at the time, based on current evidence.

最后,工程团队的决策应该归结为几件事:

- 我们这样做是因为我们必须这么做(法律要求、客户要求)。

- 我们之所以这样做,是因为根据当前证据,这是我们当时能看到的最佳选择(由一些适当的决策者决策)。

Decisions should not be “We are doing this because I said so.”17

决策不应该是“我们这样做是因为我这么说。”17

17This is not to say that decisions need to be made unanimously, or even with broad consensus; in the end, someone must be the decider. This is primarily a statement of how the decision-making process should flow for whoever is actually responsible for the decision.

这并不是说决策需要一致做出,甚至需要有广泛的共识;最终,必须有人成为决策者。这主要是说明决策过程应该如何为实际负责决策的人进行。

Inputs to Decision Making 对决策的输入

When we are weighing data, we find two common scenarios:

- All of the quantities involved are measurable or can at least be estimated. This usually means that we’re evaluating trade-offs between CPU and network, or dollars and RAM, or considering whether to spend two weeks of engineer-time in order to save N CPUs across our datacenters.

- Some of the quantities are subtle, or we don’t know how to measure them. Sometimes this manifests as “We don’t know how much engineer-time this will take.” Sometimes it is even more nebulous: how do you measure the engineering cost of a poorly designed API? Or the societal impact of a product choice?

当我们权衡数据时,我们发现两种常见情况:

- 所有涉及的数量都是可测量的或至少可以预估的。这通常意味着我们正在评估CPU和网络、美金和RAM之间的权衡,或者考虑是否花费两周的工作量,以便在我们的数据中心节省N个CPU。

- 有些数量是微妙的,或者我们不知道如何衡量。有时这表现为“我们不知道这需要多少工作量”。有时甚至更模糊:如何衡量设计拙劣的API的工程成本?或产品导致的社会影响?

There is little reason to be deficient on the first type of decision. Any software engineering organization can and should track the current cost for compute resources, engineer-hours, and other quantities you interact with regularly. Even if you don’t want to publicize to your organization the exact dollar amounts, you can still produce a conversion table: this many CPUs cost the same as this much RAM or this much network bandwidth.

在第一类决策上没有什么理由存在缺陷。任何软件工程的组织都可以并且应该跟进当前的计算资源成本、工程师工作量以及你经常接触的其他成本。即使你不想向你的组织公布确切的金额,你仍然可以制定一份版本表:这么多CPU的成本与这么多RAM或这么多网络带宽。

With an agreed-upon conversion table in hand, every engineer can do their own analysis. “If I spend two weeks changing this linked-list into a higher-performance structure, I’m going to use five gibibytes more production RAM but save two thousand CPUs. Should I do it?” Not only does this question depend upon the relative cost of RAM and CPUs, but also on personnel costs (two weeks of support for a software engineer) and opportunity costs (what else could that engineer produce in two weeks?).

有了一个协定的转换表,每个工程师都可以自己进行分析。“如果我花两周的时间将这个链表转换成一个更高性能的数据结构,我将多使用5Gb的RAM,但节省两千个CPU。我应该这样做吗?”这个问题不仅取决于RAM和CPU的相对成本,还取决于人员成本(对软件工程师的两周支持)和机会成本(该工程师在两周内还能生产什么?)。

For the second type of decision, there is no easy answer. We rely on experience, leadership, and precedent to negotiate these issues. We’re investing in research to help us quantify the hard-to-quantify (see Chapter 7). However, the best broad suggestion that we have is to be aware that not everything is measurable or predictable and to attempt to treat such decisions with the same priority and greater care. They are often just as important, but more difficult to manage.

对于第二类决策,没有简单的答案。我们依靠经验、领导作风和先例来协商这些问题。我们正在投入研究,以帮助我们量化难以量化的问题(见第7章)不过,我们所能提供的最好的广泛建议是,意识到并非所有的事情都是可衡量或可预测的,并尝试以同样的优先级和更谨慎得对待此类决策。它们往往同样重要,但更难管理。

Example: Distributed Builds 示例:分布式构建

Consider your build. According to completely unscientific Twitter polling, something like 60 to 70% of developers build locally, even with today’s large, complicated builds. This leads directly to nonjokes as illustrated by this “Compiling” comic—how much productive time in your organization is lost waiting for a build? Compare that to the cost to run something like distcc for a small group. Or, how much does it cost to run a small build farm for a large group? How many weeks/months does it take for those costs to be a net win?

考虑到你的构建。根据不可靠的推特投票结果显示,大约有60到70%的开发者在本地构建,即使是今天的大型、复杂的构建。才有了这样的笑话,如“编译”漫画所示。你的组织中有多少时间被浪费在等待构建上?将其与为一个小团队运行类似distcc的成本进行比较。或者,为一个大团队运行一个小构建场需要多少成本?这些成本需要多少周/月才能成为一个净收益?

Back in the mid-2000s, Google relied purely on a local build system: you checked out code and you compiled it locally. We had massive local machines in some cases (you could build Maps on your desktop!), but compilation times became longer and longer as the codebase grew. Unsurprisingly, we incurred increasing overhead in personnel costs due to lost time, as well as increased resource costs for larger and more powerful local machines, and so on. These resource costs were particularly troublesome: of course we want people to have as fast a build as possible, but most of the time, a high- performance desktop development machine will sit idle. This doesn’t feel like the proper way to invest those resources.

早在2000年代中期,谷歌就完全依赖于本地构建系统:你切出代码,然后在本地编译。在某些情况下,我们有大量的本地机器(你可以在桌面电脑上构建地图!),但随着代码库的增长,编译时间变得越来越长。不出所料,由于时间的浪费,我们的人员成本增加,以及更大、更强大的本地机器的资源成本增加等等。这些资源成本特别麻烦:当然,我们希望人们有一个尽可能快的构建,但大多数时候,一个高性能的桌面开发机器将被闲置。这感觉不像是投资这些资源的正确方式。

Eventually, Google developed its own distributed build system. Development of this system incurred a cost, of course: it took engineers time to develop, it took more engineer time to change everyone’s habits and workflow and learn the new system, and of course it cost additional computational resources. But the overall savings were clearly worth it: builds became faster, engineer-time was recouped, and hardware investment could focus on managed shared infrastructure (in actuality, a subset of our production fleet) rather than ever-more-powerful desktop machines. Chapter 18 goes into more of the details on our approach to distributed builds and the relevant trade-offs.

最终,谷歌开发了自己的分布式构建系统。开发这个系统当然要付出代价:工程师花费了时间,工程师花更多的时间来改变每个人的习惯和工作流程,学习新系统,当然还需要额外的计算资源。但总体节约显然值得我去做: 构建速度变快了,工程师的时间被节约了,硬件投资可以集中在管理的共享基础设施上(实际上是我们生产机群的一个子集),而不是日益强大的桌面机。第18章详细介绍了我们的分布式构建方法和相关权衡。

So, we built a new system, deployed it to production, and sped up everyone’s build. Is that the happy ending to the story? Not quite: providing a distributed build system made massive improvements to engineer productivity, but as time went on, the distributed builds themselves became bloated. What was constrained in the previous case by individual engineers (because they had a vested interest in keeping their local builds as fast as possible) was unconstrained within a distributed build system. Bloated or unnecessary dependencies in the build graph became all too common. When everyone directly felt the pain of a nonoptimal build and was incentivized to be vigilant, incentives were better aligned. By removing those incentives and hiding bloated dependencies in a parallel distributed build, we created a situation in which consumption could run rampant, and almost nobody was incentivized to keep an eye on build bloat. This is reminiscent of Jevons Paradox: consumption of a resource may increase as a response to greater efficiency in its use.

因此,我们构建了一个新系统,将其部署到生产环境中,并加快了每个人的构建速度。这就是故事的圆满结局吗?不完全是这样:提供分布式构建系统极大地提高了工程师的工作效率,但随着时间的推移,分布式构建本身变得臃肿起来。在以前的情况下,单个工程师受到的限制(因为他们尽最大可能保持本地构建的速度)在分布式构建系统中是不受限制的。构建图中的臃肿或不必要的依赖关系变得非常普遍。当每个人都直接感受到非最佳构建的痛苦,并被要求去保持警惕时,激励机制会更好地协调一致。通过取消这些激励措施,并将臃肿的依赖关系隐藏在并行的分布式构建中,我们创造了一种情况,在这种情况下,消耗可能猖獗,而且几乎没有人被要求去关注构建的臃肿。这让人想起杰文斯悖论(Jevons Paradox):一种资源的消耗可能会随着使用效率的提高而增加。

Overall, the saved costs associated with adding a distributed build system far, far outweighed the negative costs associated with its construction and maintenance. But, as we saw with increased consumption, we did not foresee all of these costs. Having blazed ahead, we found ourselves in a situation in which we needed to reconceptualize the goals and constraints of the system and our usage, identify best practices (small dependencies, machine-management of dependencies), and fund the tooling and maintenance for the new ecosystem. Even a relatively simple trade-off of the form “We’ll spend $$$s for compute resources to recoup engineer time” had unforeseen downstream effects.

总的来说,与添加分布式构建系统相关的节省成本远远超过了与其构建和维护相关的负成本。但是,正如我们看到的消耗增加,我们并没有以前预见到这些成本。勇往直前之后,我们发现自己处于这样一种境地:我们需要重新认识系统的目标和约束以及我们的使用方式,确定最佳实践(小型依赖项、依赖项的机器管理),并为新生态系统的工具和维护提供资金。即使是相对简单的 "我们花美元购买计算资源以收回工程师时间 "的权衡,也会产生不可预见的下游影响。

Example: Deciding Between Time and Scale 示例:在时间和规模之间做决定

Much of the time, our major themes of time and scale overlap and work in conjunction. A policy like the Beyoncé Rule scales well and helps us maintain things over time. A change to an OS interface might require many small refactorings to adapt to, but most of those changes will scale well because they are of a similar form: the OS change doesn’t manifest differently for every caller and every project.

很多时候,我们关于时间和规模的主题相互重合,相互影响。符合碧昂斯规则策略具备可扩展性,并帮助我们长期维护事物。对操作系统接口的更改需要许多小的重构来适应,但这些更改中的大多数都可以很好地扩展,因为它们具有相似的形式: 操作系统的变化对每个调用者和每个项目都没有不同的表现。

Occasionally time and scale come into conflict, and nowhere so clearly as in the basic question: should we add a dependency or fork/reimplement it to better suit our local needs?

有时,时间和规模的考量会发生冲突,尤其是在这样一个基本问题上:我们应该添加一个外部依赖,还是对其进行分支或重新实现,以更好地满足我们的本地需求?

This question can arise at many levels of the software stack because it is regularly the case that a bespoke solution customized for your narrow problem space may outperform the general utility solution that needs to handle all possibilities. By forking or reimplementing utility code and customizing it for your narrow domain, you can add new features with greater ease, or optimize with greater certainty, regardless of whether we are talking about a microservice, an in-memory cache, a compression routine, or anything else in our software ecosystem. Perhaps more important, the control you gain from such a fork isolates you from changes in your underlying dependencies: those changes aren’t dictated by another team or third-party provider. You are in control of how and when to react to the passage of time and necessity to change.

这个问题可能出现在软件栈(解决方案栈)各个层面,通常情况下,为特定问题定制解决方案优于需要处理所有问题的通用解决方案。通过分支或重新实现程序代码,并为特定问题定制它,你可以更便捷地添加新功能,或更确定地进行优化,无论我们谈论的是微服务、内存缓存、压缩程序还是软件生态系统中的其他内容。更重要的是,你从这样一个分支中获得的控制将你与基础依赖项中的变更隔离开:这些变化并不是由另一个团队或第三方供应商所决定的。你随时决定如何对时间的推移和变化的作出必要地反应。

[一条微博引发的思考——再谈“Software Stack”之“软件栈”译法!](https://www.ituring.com.cn/article/1144)

软件栈(Software Stack),是指为了实现某种完整功能解决方案(例如某款产品或服务)所需的一套软件子系统或组件。

On the other hand, if every developer forks everything used in their software project instead of reusing what exists, scalability suffers alongside sustainability. Reacting to a security issue in an underlying library is no longer a matter of updating a single dependency and its users: it is now a matter of identifying every vulnerable fork of that dependency and the users of those forks.

另一方面,如果每个开发人员都将他们的软件项目中使用的组件是多样化,而不是复用现有的组件,那么可扩展性和可持续性都会受到影响。对底层库中的安全问题作出反应不再是更新单个依赖项及其用户的问题:现在要做的是识别该依赖关系的每一个易受攻击的分支以及使用这个分支的用户。

As with most software engineering decisions, there isn’t a one-size-fits-all answer to this situation. If your project life span is short, forks are less risky. If the fork in question is provably limited in scope, that helps, as well—avoid forks for interfaces that could operate across time or project-time boundaries (data structures, serialization formats, networking protocols). Consistency has great value, but generality comes with its own costs, and you can often win by doing your own thing—if you do it carefully.

与大多数软件工程决策一样,对于这种情况并没有一个一刀切的答案。如果你的项目生命周期很短,那么fork的风险较小。 如果有问题的分支被证明是范围有限的,那是有帮助的,同时也要避免分支那些可能跨越时间段或项目时间界限的接口(数据结构、序列化格式、网络协议)。一致性有很大的价值,但通用性也有其自身的成本,你往往可以通过做自己的事情来赢得胜利——如果你仔细做的话。

Revisiting Decisions, Making Mistakes 重审决策,标记错误

One of the unsung benefits of committing to a data-driven culture is the combined ability and necessity of admitting to mistakes. A decision will be made at some point, based on the available data—hopefully based on good data and only a few assumptions, but implicitly based on currently available data. As new data comes in, contexts change, or assumptions are dispelled, it might become clear that a decision was in error or that it made sense at the time but no longer does. This is particularly critical for a long-lived organization: time doesn’t only trigger changes in technical dependencies and software systems, but in data used to drive decisions.

致力于数据驱动文化的一个不明显的好处是承认错误的能力和必要性相结合。在某个时候,将根据现有的数据做出决定——希望是基于准确的数据和仅有的几个假设,但隐含的是基于目前可用的数据。随着新数据的出现,环境的变化,或假设的不成了,可能会发现某个决策是错误的,或在当时是有意义的,但现在已经没有意义了。这对于一个长期存在的组织来说尤其重要:时间不仅会触发技术依赖和软件系统的变化,还会触发用于驱动决策的数据的变化。

We believe strongly in data informing decisions, but we recognize that the data will change over time, and new data may present itself. This means, inherently, that decisions will need to be revisited from time to time over the life span of the system in question. For long-lived projects, it’s often critical to have the ability to change directions after an initial decision is made. And, importantly, it means that the deciders need to have the right to admit mistakes. Contrary to some people’s instincts, leaders who admit mistakes are more respected, not less.

我们坚信数据能为决策提供信息,但我们也认识到数据会随着时间的推移而变化,新数据可能会出现。这意味着,本质上,在相关系统的生命周期内,需要不时地重新审视决策。对于长期项目而言,在做出初始决策后,有能力改变方向通常是至关重要的。更重要的是,这意味着决策者需要勇气承认错误。与人的直觉相反,勇于承认错误的领导人受更多的尊重。

Be evidence driven, but also realize that things that can’t be measured may still have value. If you’re a leader, that’s what you’ve been asked to do: exercise judgement, assert that things are important. We’ll speak more on leadership in Chapters 5 and 6.

以证据为导向,但也要意识到无法衡量的东西可能仍然有价值。如果你是一个领导者,那就是你被要求做的:审时度势,主张事在人为。我们将在第5章和第6章中详细介绍领导力

Software Engineering Versus Programming 软件工程与编程

When presented with our distinction between software engineering and programming, you might ask whether there is an inherent value judgement in play. Is programming somehow worse than software engineering? Is a project that is expected to last a decade with a team of hundreds inherently more valuable than one that is useful for only a month and built by two people?

在介绍软件工程和编程之间的区别时,你可能会问,是否存在内在的价值判断。编程是否比软件工程更糟糕?一个由数百人组成的团队预计将持续十年的项目是否比一个只有一个月的项目和两个人构建的项目更有价值?

Of course not. Our point is not that software engineering is superior, merely that these represent two different problem domains with distinct constraints, values, and best practices. Rather, the value in pointing out this difference comes from recognizing that some tools are great in one domain but not in the other. You probably don’t need to rely on integration tests (see Chapter 14) and Continuous Deployment (CD) practices (see Chapter 24) for a project that will last only a few days. Similarly, all of our long-term concerns about semantic versioning (SemVer) and dependency management in software engineering projects (see Chapter 21) don’t really apply for short-term programming projects: use whatever is available to solve the task at hand.

当然不是。我们的观点并不是说软件工程是优越的,只是它们代表了两个不同的问题领域,具有不同的约束、价值和最佳实践。相反,指出这种差异的价值来自于认识到一些工具在一个领域是伟大的,但在另一个领域不是。对于只持续几天的项目,你不需要依赖集成测试(参见第14章)和持续部署(CD)实践(参见第24章)。同样地,我们对软件工程项目中的版本控制(SemVer)和依赖性管理(参见第21章)的所有长期关注,并不适用于短期编程项目:利用一切可以利用的手段来解决手头的任务。

We believe it is important to differentiate between the related-but-distinct terms “programming” and “software engineering.” Much of that difference stems from the management of code over time, the impact of time on scale, and decision making in the face of those ideas. Programming is the immediate act of producing code. Software engineering is the set of policies, practices, and tools that are necessary to make that code useful for as long as it needs to be used and allowing collaboration across a team.

我们认为,区分相关但不同的术语“编程”和“软件工程”是很重要的。这种差异很大程度上源于随着时间的推移对代码的管理、时间对规模的影响以及面对这些想法的决策。编程是产生代码的直接行为。软件工程是一组策略、实践和工具,这些策略、实践和工具是使代码在需要使用的时间内发挥作用,并允许整个团队的协作。

Conclusion 总结

This book discusses all of these topics: policies for an organization and for a single programmer, how to evaluate and refine your best practices, and the tools and technologies that go into maintainable software. Google has worked hard to have a sustainable codebase and culture. We don’t necessarily think that our approach is the one true way to do things, but it does provide proof by example that it can be done. We hope it will provide a useful framework for thinking about the general problem: how do you maintain your code for as long as it needs to keep working?

本书讨论了所有这些主题:一个组织和一个程序员的策略,如何评估和改进你的最佳实践,以及用于可维护软件的工具和技术。谷歌一直在努力打造可持续的代码库和文化。我们不认为我们的方法是做事情的唯一正确方法,但它确实通过例子证明了它是可以做到的。我们希望它将提供一个有用的框架来思考一般问题:你如何维护你的代码,让它正常运行。

TL;DRs 内容提要

-

Software engineering” differs from “programming” in dimensionality: programming is about producing code. Software engineering extends that to include the maintenance of that code for its useful life span.

-

There is a factor of at least 100,000 times between the life spans of short-lived code and long-lived code. It is silly to assume that the same best practices apply universally on both ends of that spectrum.

-

Software is sustainable when, for the expected life span of the code, we are capable of responding to changes in dependencies, technology, or product requirements. We may choose to not change things, but we need to be capable.

-

Hyrum’s Law: with a sufficient number of users of an API, it does not matter what you promise in the contract: all observable behaviors of your system will be depended on by somebody.

-

Every task your organization has to do repeatedly should be scalable (linear or better) in terms of human input. Policies are a wonderful tool for making process scalable.

-

Process inefficiencies and other software-development tasks tend to scale up slowly. Be careful about boiled-frog problems.

-

Expertise pays off particularly well when combined with economies of scale.

-

"Because I said so"” is a terrible reason to do things.

-

Being data driven is a good start, but in reality, most decisions are based on a mix of data, assumption, precedent, and argument. It’s best when objective data makes up the majority of those inputs, but it can rarely be all of them.

-

Being data driven over time implies the need to change directions when the data changes (or when assumptions are dispelled). Mistakes or revised plans are inevitable.

-

“软件工程”与“编程”在维度上不同:编程是关于编写代码的。软件工程扩展了这一点,包括在代码的生命周期内对其进行维护。

-

短期代码和长期代码的生命周期之间至少有100,000倍的系数。假设相同的最佳实践普遍适用于这一范围的两端是愚蠢的。

-

在预期的代码生命周期内,当我们能够响应依赖关系、技术或产品需求的变化时,软件是可持续的。我们可能选择不改变事情,但我们需要有能力。

-

海勒姆定律:当一个 API 有足够的用户的时候,在约定中你承诺的什么都无所谓,所有在你系统里面被观察到的行为都会被一些用户直接依赖。

-

你的组织重复执行的每项任务都应在人力投入方面具有可扩展性(线性或更好)。策略是使流程可伸缩的好工具。

-

流程效率低下和其他软件开发任务往往会慢慢扩大规模。小心煮青蛙的问题。

-

当专业知识与规模经济相结合时,回报尤其丰厚。

-

“因为我说过”是做事的可怕理由。

-

数据驱动是一个良好的开端,但实际上,大多数决策都是基于数据、假设、先例和论据的混合。最好是客观数据占这些输入的大部分,但很少可能是全部。

-

随着时间的推移,数据驱动意味着当数据发生变化时(或假设消除时),需要改变方向。错误或修订的计划不在表中。